Acorns to Oak Trees/Part 2

When you think about it, it's miraculous how a small seed – like an acorn – contains the full genetic instruction set to become something big, beautiful and life nourishing — like an oak tree. It’s an example of the gift all life forms possess: An encoded ability to reach, under the right conditions, their full potential.

It’s worth reflecting on how this “encoded ability” applies to humans.

“The true nature of anything is the highest it can become.”

— Aristotle

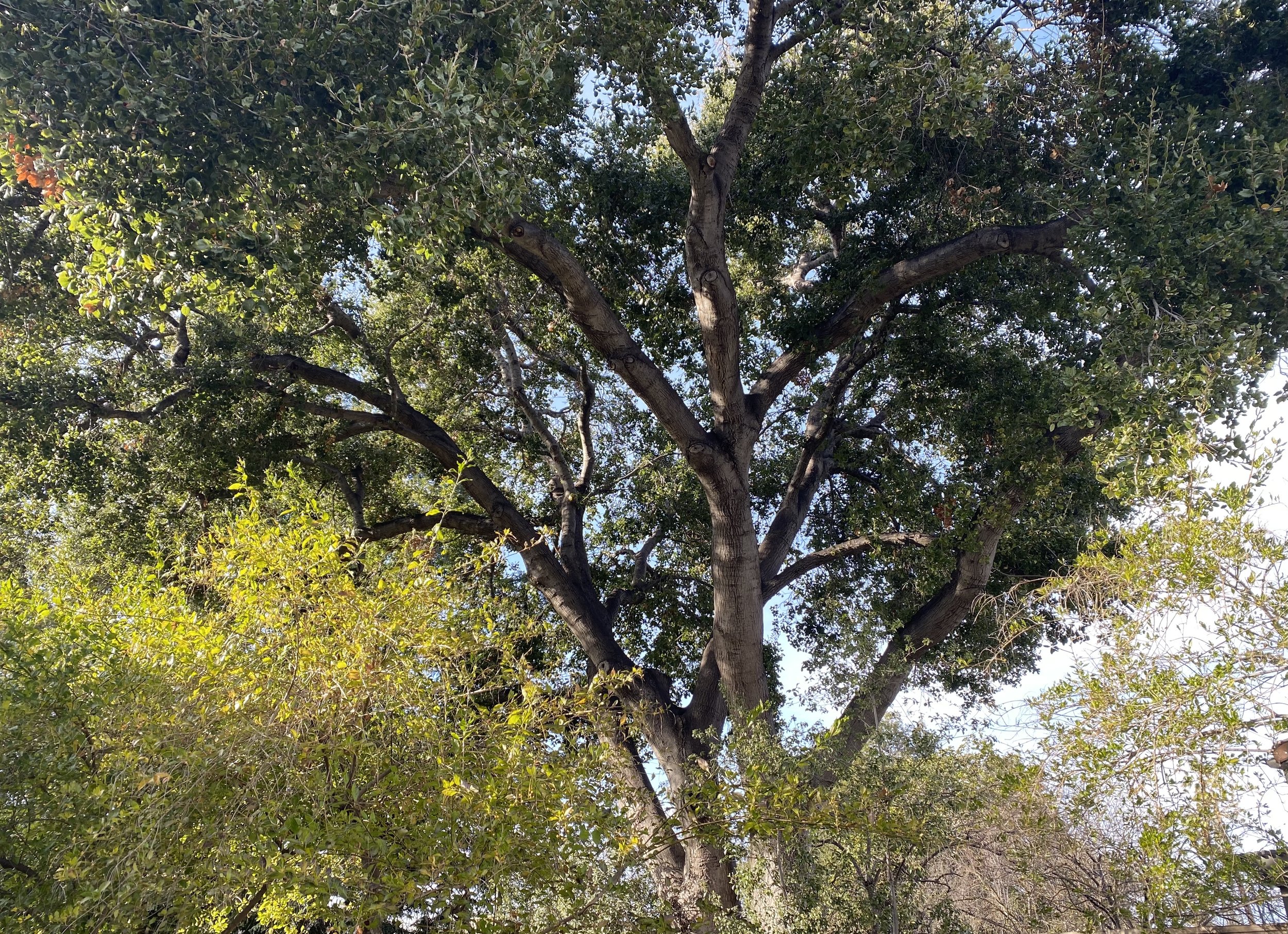

The oak tree I see outside my window as I write this post.

When you think about it, it's miraculous how a small seed – like an acorn – contains the full genetic instruction set to become something big, beautiful and life nourishing — like an oak tree. It’s an example of the gift all life forms possess: An encoded ability to reach, under the right conditions, their full potential.

It’s worth reflecting on how this “encoded ability” applies to humans. In our physical development — the trajectory from conception to adulthood — it appears obvious. But what about our psycho-social development? Once we’ve reached adulthood physically, have we also reached the peak of our mental, emotional and spiritual capacities, or is more potential available to us? And if there is, what is the nature of that potential, and what conditions help facilitate it?

Those are huge questions and it can be difficult to know where to even begin to answer them. Fortunately, a series of findings in neuroscience offer a helpful starting point.

The first of these findings has to do with how our personal experiences help shape the way our brain is structured:

“Everything that you experience leaves its mark on your brain. When you learn something new, the neurons involved in the learning episode grow new projections and form new connections.” 1

The connections not only shape how we see and interact with the world, they also help determine our brain’s overall degree of neural integration: The extent and strength of the communication pathways that connect the various regions of our brain.

The second finding is that the degree of brain integration is a reliable indicator of our overall physical, emotional and psychological wellbeing, according to research from the Human Connectome Project, funded by the National Institute of Health. In the words of Dr. Dan Siegel, UCLA Clinical Professor of Psychiatry:

“The Human Connectome project has shown that the best predictor of a wide range of measures of well-being is how interconnected the connectome is – that is, how integrated the brain is.”2

The best predictor of wellbeing is how integrated our brain is.

While impaired neural integration is associated with a host of disorders characterized by rigidity, chaos and emotional reactivity, increased neural integration is associated with a host of positive attributes including greater resiliency, flexibility and adaptability, all expressed outwardly, says Siegel, as "harmony, kindness and compassion.”3

If you believe, like I do, that the world sorely needs more harmony, kindness and compassion — on every side of every divide, for the sake of ourselves, our children and our planet — then you’ll be especially interested in the third and last finding I want to share: We all have an “encoded ability” to increase our own neural integration.

In short, we are wired to rewire — an ability made possible by what science calls neuroplasticity: The capacity of our brain "to modify, change, and adapt both structure and function throughout life and in response to experience.”4

In other words, no matter who we are, we can actually create for ourselves experiences and conditions that facilitate our own evolution in the direction most needed for our individual and collective wellbeing.

What’s more, nothing is preventing us from exercising this ability. No one else needs to go first. No laws need to be created or repealed. No special permissions are required. All that’s needed is our individual, autonomous decision to take responsibility for our own further evolution — to move in the direction of “the highest we can become.”

So what are the experiences and conditions that facilitate greater neural integration, and what impact might it have on our collective future? That’s what we’ll explore in my next post.

As always, thanks for reading.

Kern

1 https://elifesciences.org/digests/52743/how-experience-shapes-the-brain

2 https://wilddivine.com/blogs/news/how-integrating-your-brain-creates-a-more-resilient-life

3 https://drdansiegel.com/

4 https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01657/full

Acorns to Oak Trees: A Metaphor for Better Times Ahead

A good metaphor can change how you see the world.

A good metaphor can change how you see the world.

This one is from a meteorologist, who used it to illustrate how far data modeling tools have come. He said that a few decades ago if you asked meteorologists what an acorn would look like sometime in the future, “their answer would essentially be a much bigger acorn...

“Today, they would show you an oak tree.”

I find that metaphor helpful because, with a couple tweaks, it applies to another kind of data modeling tool: the human imagination. It’s one way humans “predict” the future. First we imagine it and then, if possible, create it. And while theoretically we could imagine any number of possible futures for our species, what we often end up with are just bigger acorns. A few examples:

Gas cars become electric cars, become self-driving cars, become flying cars (?). Interesting, but it’s a future in which we’re still transporting ourselves in cars, doing the damage that cars do — and it’s far more than just emitting CO2. Bigger acorns.

Oil energy becomes solar and wind energy, becomes cold fusion energy (?). Helpful, sure. But whatever the source, we’re still using that energy to fuel an economic system that undermines nature’s life support system. In that sense, bigger acorns.

Weapons that kill hundreds become weapons that kill thousands, become weapons that kill millions, become weapons that kill billions. (Meanwhile, soldiers become AI robots?). Needless to say, bigger acorns.

So what data is missing from our “imagination modeling tool” that we can’t break out of this pattern? Why are we just imagining bigger acorns when the power is in our hands to imagine something entirely different, something more life affirming?

The answer, I suggest, is that our imagination model does not adequately account for our ability to evolve beyond our tribal mentality and our rapacious and militaristic instincts. And as long as we deny that possibility for ourselves, we’ll keep imagining and creating bigger acorns, rather than beautiful, life-nurturing oak trees.

Now, some people — perhaps a lot of people — believe such an evolutionary step for humanity is impossible. But holding that view requires two things:

Excusing from our data set those who have taken that step, declaring them extraordinary in some way.

Ignoring what we’re discovering in the fields of neuropsychology and neurobiology about the human brain and our innate capacity for change. (Discoveries that, by the way, find striking alignment with wisdom teachings stretching back 3,000 years and codified in almost all spiritual traditions.)

In upcoming posts I’ll explore some of these discoveries in more detail and how we might apply them to our own growth process. Because if we can validate for ourselves that our future can look a lot more like oak trees, we can begin in earnest to imagine the tools, institutions and customs that will support it.

Until then, two inspiring media recommendations that highlight our capacity for change and the promising future it can produce:

Stranger at the Gate: A powerful 30 minute documentary about a former Marine suffering from post traumatic stress, and how his plan to attack a community of Muslims in Indiana became a journey of self-healing and forgiveness.

A Revelatory Tour of Martin Luther King Jr.’s Forgotten Teachings: The latest podcast from Ezra Klein. His guest is Harvard University professor Brandon Terry, co-editor of “To Shape a New World: Essays on the Political Philosophy of Martin Luther King Jr.” It’s a rich, thoughtful, and provocative interview. An excerpt:

“What you have to be committed to, in the last instance, is that evil is not the totality of who we are as persons, that people have the capacity, emotionally and rationally, to reflect on their life plans, their practices, their commitments, and change them, maybe not all of them, maybe not all at once, but that those things can be changed, and that …the unprecedented, the new, the unexpected, happens in this realm.

“And the only way that we can confirm that nothing new will happen, that oppression will last forever, that the future bears no hope, is if we don’t act. That’s the only way we can confirm that it’s true for all time…”

Thanks for reading, and best wishes to you and yours for a healthy and joyous 2023.

The Logic of Nonviolence: Lessons from a 5-year-old, revisited.

Retaliation is a natural human instinct. Hurt me and I’ll want to hurt you back. Not only does this act of revenge give me a short-lived, dopamine-infused jolt of satisfaction, it also, hopefully, convinces you not to hurt me again. It's that hope, however, that often proves unfounded.

Years ago I was bouncing on the trampoline with my then five year old son, when he became a bit too exuberant and accidentally kicked me in the crotch. In pain – and perceiving his transgression as an act of carelessness – I instantly retaliated by giving him a light swat on his behind. That it was a light swat didn’t matter — the injury I inflicted was more emotional than physical. Stunned by my un-fatherly behavior, my son glared at me with the eyes of the betrayed. “You’re an adult,” he said. “Adults don’t hit children.”

My shame was instant.

Retaliation is a natural human instinct. Hurt me and I’ll want to hurt you back. Not only does this act of revenge give me a short-lived, dopamine-infused jolt of satisfaction, it also, hopefully, convinces you not to hurt me again.

It's that hope, however, that often proves unfounded. Rather than convincing you to back down, it does the opposite: Now you want to retaliate, setting in motion a cycle of violence that too often ends in unnecessary harm and even tragedy.

That of course is the lesson of war — a lesson we've repeated so many times it's amazing we still haven't gotten the point. So why not? One big reason is because we don't see any viable alternative. If I don't match or exceed your level of violence, how else do I take away your power to hurt me?

Well, the fact is there are alternatives. Effective alternatives. Which brings me to my podcast guest this month, political scientist Maria J. Stephan.

Co-Lead and Chief Organizer at The Horizons Project and the former Director of the Program on Nonviolent Action at the United States Institute of Peace, Maria Stephan is the co-author (with Erica Chenoweth) of the award-winning book, Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict. The book shares the result of more than two years of research focused on the question: can nonviolent civil resistance be successful even against the most militarily sophisticated and brutal regimes? Their answer, based on analyzing over 330 violent and nonviolent campaigns, is an unequivocal "yes." In fact, they found that nonviolent campaigns were twice as effective as violent ones in achieving their political goals.

It's a stunning finding. And at a time when the war in Ukraine threatens the entire planet with a nuclear catastrophe, and when political turmoil in the U.S. has people wondering if we're headed toward a civil war, it's a finding that, more than ever, is essential to our collective future.

So please, check out my podcast with Maria Stephan. In the first half you’ll learn about what non-violent action is, why it’s so powerful, the forces working against non-violent action today, and how those forces can be overcome. In the second half Stephan talks about her current work at The Horizons Project, which focuses on the threat of authoritarianism in the United States. She discusses the U.S.’s long history of authoritarian tendencies, exactly how those tendencies are manifesting today, and how the tools and strategies of nonviolent action can be used to effectively counter them.

In addition to the podcast, below are two other resources on non-violent action that you may find particularly of interest.

A Force More Powerful is a two-part, multiple-award-winning documentary series “on one of the 20th century’s most important and least-known stories: how nonviolent power overcame oppression and authoritarian rule. It includes six cases of movements, and each case is approximately 30 minutes long.” This is the documentary that motivated Maria to study nonviolent movements.

The Strength of Nonviolence in Ukraine. Yes, there’s a war in Ukraine. But as Maria mentions in the podcast, there’s also a very strong, rarely covered nonviolent movement as well. This website is a rich resource on the effectiveness of nonviolent action, even, and perhaps especially, in the midst of war.

If i’ve learned anything, it’s this.

I’ll never forget my first “official” Difficult Conversations workshop – the first real test of whether I’d created something of value.

November 2017: My first Difficult Conversations workshop, in Redding, California.

I’ll never forget my first “official” Difficult Conversations workshop – the first real test of whether I’d created something of value. It was in November 2017. Eighty city leaders from the mostly-conservative town of Redding, California attended. In hindsight, probably not the most strategic gathering for my workshop’s maiden voyage, but it went well. I even remember getting a standing ovation at the end — although to be honest, there’s a chance most people were simply clapping as they stood up to leave. Still, it was a success, and it gave me the confidence I needed to continue developing the workshop and seek out new opportunities to lead it.

Now, five years later, I’ve led the workshop more than 100 times for diverse groups around the U.S. and even internationally. And if I’ve learned anything, it’s this: If you offer people helpful, well-researched and even challenging information in a respectful, safe and kind environment, they will listen, engage, and give the material their full consideration. And far more often than not, they'll be changed by the experience.

Over the years, the workshop has also changed – adjustments and additions that have helped clarify the major concepts. Often the impetus for these changes came from the insights and feedback from the participants themselves. Other times they came from my own ah-ha moments, when I connected with the material in a new and deeper way. And still other times they came from immersing myself in the work of others, and finding ways to integrate their insights and discoveries.

One recent example of the latter is a framework called The Three Dimensions of Difficult Conversations, from the book Difficult Conversations: How to discuss what matters most. It’s a powerful framing that, as one person put it, “makes it easy to understand why some difficult conversations move relationships forward and others have the opposite impact.” The short video above provides an overview of this framework that you might find helpful.

It’s all been a rich and rewarding experience, but that said, it now seems I’ve hit a lull. For the first time I have no future workshops on the calendar. I don’t mind. I could use a break, and I have a feeling I’m not alone. Perhaps there’s a collective sense that we all need to take a breath, to get out of crisis mode, to let the 2022 midterms take the temperature of the American public, and then see what needs emerge.

At least, that’s where I am right now. I’m going to take some time to travel, read, and try a few new things. I’ll do the workshop when asked, but otherwise I’ll be reflecting on what’s next and where my time is best spent.

As part of that I’ll keep going with my podcast. My next guest is Maria Stephan, co-leader of The Horizons Project and former Director of the program on nonviolent action at the United States Institute of Peace. She’s also the author, together with Erica Chenoweth, of the seminal 2010 book Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict. It should be a fascinating and timely conversation. I’ll be interviewing Maria in October.

Listening as a “creative force”

I don’t know if you’ve noticed, but people in general are not good listeners. One reason might be that we stop listening to each other almost the moment a conversation has begun.

I don’t know if you’ve noticed, but people in general are not good listeners. One reason might be that we stop listening to each other almost the moment a conversation has begun.

In a typical conversation, say the experts, the average gap between one person speaking and the other person responding is an unbelievable 200 milliseconds. That’s not enough time to form a thought let alone speak it. So how do we do it? Simple. By preparing our responses while the other person is still talking.

Contrary to popular belief, humans cannot multi-task, so if we’re busy forming our opinion before the other person has finished their thought, there isn't much listening going on. Which may help explain why, on average, we only listen with 25% efficiency. Imagine only being able to see 25% of what you’re looking at. You’d be missing a huge part of the picture.

From an evolutionary perspective, of course, it’s reasonable to assume that this 200 millisecond interval must have once given our species some sort of survival advantage. Times change, however, and in today’s world it’s clear that our preference for speaking over listening is a serious survival disadvantage. The more we fail to listen to each other, the wider the gulf between us, and the less able we are to address our many challenges.

Which is why I think of listening as the survival skill of the 21st century.

Now for some people that statement will rub them the wrong way – they think the time for listening has passed, and that what we most need now is action. I partially agree. I’d say that the time for listening with only 25% comprehension has passed. What’s needed now is to take listening to a whole new level – the level at which listening becomes, in the words of my latest podcast guest, Kay Lindahl, a creative force.

Kay Lindahl

Kay is the founder of The Listening Center and the author of The Sacred Art of Listening. One reason she calls listening a creative force is because it has the power to change both the listener and the person being listened to. That’s because, also contrary to what most people think, people learn when they talk. Especially when they’re asked the right questions. Not entrapment questions, but genuinely curious questions — questions that help people discover the assumptions and motivations that, until someone asked, were hidden from them. It’s at that level of listening that hearts and minds begin to change.

By listening in this way, says Kay:

We become the midwife for someone else's thinking. So the space that we can offer, as a listener, gives someone the space to really speak from their deepest selves, and discover things about themselves that they might not have known before.

This kind of listening, however, takes practice. After all, having two ears does not make us a good listener any more than having two legs makes us an olympic runner. Says Kay:

Holding the space for someone to speak their truth takes practice. It's not easy to [hold that space] because it means we have to let go of our own agenda, our own thoughts — for the moment — so that we can be fully present to the other person.

Developing such a practice is the focus of Kay’s training, and her approach is unusual. Rather than teach specific listening skills or methodologies, Kay teaches how to develop what she calls “a listening presence.” And that, she says, is more art than technique:

Think about a time when someone was really listening to you. They weren't thinking about what they were going to say next, or what they were going to do next, or where they were going to go. They were really present. How did that make you feel?

Most people say it made them feel heard, validated, loved, cared for, nurtured, valued — all those kinds of things. And those are experiences where we feel ‘at one’ with somebody else, there's a oneness to those experiences.

And that's when I think listening shifts from something that we do, to something that we be — so we become a listening presence. And that's the art.

To learn more about what Kay has to teach, I highly recommend listening to our entire conversation. You’ll find it here.

Reflections on Self-Righteousness

I’ve been thinking more about what keeps us from being in dialogue with those we disagree with. One cause that stands out: Self-righteousness.

I’ve been thinking more about what keeps us from being in dialogue with those we disagree with. One cause that stands out: Self-righteousness.

What got me thinking about self-righteousness was listening to a podcast based on the popular TV series, Brooklyn 99. The podcast features the show’s creators, writers and cast members as they reflect on their experiences filming some of the show's more memorable scenes. One of the scenes they discuss features the African-American actor Terry Crews. Terry plays a cop on the show, and in one episode his character is subjected to racial profiling by another cop, who’s White. Preparing for that scene, said Terry, led to a surprising insight:

The terms “racism” and “hate” get thrown around a lot — you know, “they hate me, and it's racism.” But then I read a quote from Winston Churchill – who was often accused of being racist himself – who said that when people do something heinous and violent to other people, we may think it’s because they hate them, but really all of the intense violence and callousness comes from self-righteousness.

And that blew me away. That was a whole other thing. And I was like, wait a minute! The common belief is that you're abusing me, you're hurting me, because you hate me. But really, it’s not hate at all. It's the fact that you believe that you’re right. You believe you are so right, that you can do this to people…you have the authority to do it.”

That changed the whole picture…it gave me a different perspective. Because hey, it's hard to imagine yourself hating people. But you can imagine at some time in your life being self-righteous. You know what I mean? Because everyone at one time or another has felt like, “Hey, I am right. I am right, here!”

Like Terry, I find this a helpful and revealing insight. It connects what might appear to be an incomprehensible, hate-filled act of violence to what is a very comprehensible, and ubiquitous, human attribute: self-righteousness. Suddenly one root of a large and overwhelming social ill is found a little closer to home. As Terry says, everyone at one time or another has felt self-righteous – when our certainty of being right justified dismissing or mistreating another human being, even if only in subtle and indirect ways.

I know I’ve had many such experiences. Usually it involves an encounter with someone who believes something I judge to be egregiously ignorant, harmful, insensitive, privileged, wrong. In those situations, being so sure of my rightness made it easy for me to treat that person with disdain and disrespect.

Now some people might say this is all a false equivalency, that behaviors that lead to violent atrocities are not the same as behaviors that lead to, say, merely being rude and dismissive. That’s certainly true.

But to take a lesson from nature, everything big is an aggregation of things that are small. All life is built on that pattern. So too is culture – an aggregation, ultimately, of individual human interactions. So if we want to solve society’s large-scale problems, we can start by establishing the small-scale patterns that, as they build and multiply, will allow us to do so.

Compassion and understanding, rather than self-righteous judgment, are two such ‘small-scale patterns,’ and the ones most likely to emerge when we fully embrace the notion that “as I am, so the world is.”

So what can we do when we find ourselves in the grip of our self-righteous impulses? One way I’ve found helpful is to not feel I need to “own” my beliefs, but rather to regard them as I would a beautiful work of art: from a distance. I can value it, I can let it influence me, I can tell others about it. But what I’m not going to do is grab it off the wall and bang it over someone’s head until they see it the way I do.

why journalists only tell us half the story

They may not think of themselves this way, but journalists are storytellers, and the way they tell their stories shapes how you and I see each other and our world. The problem, however, is that journalists usually tell us only half the story – leaving us with a very distorted view of reality. A new approach called Solutions Journalism fills in the picture.

“The universe is not made of atoms; it's made of stories.”

― Muriel Rukeyser

Like a lot of people, I find the news these days dispiriting. But it’s not just the events being reported that I find depressing, it’s the way they’re being reported: scored with a relentless drumbeat of negativity that makes me feel as if I’m being marched to the edge of an abyss, only to be left there alone to contemplate our increasingly bleak future.

They may not think of themselves this way, but journalists are storytellers, and the way they tell their stories shapes how you and I see each other and our world. The problem, however, is that journalists usually tell us only half the story – leaving us with a very distorted view of reality.

The dystopian vision much of our media creates does not happen by accident. It’s the result of what my latest podcast guest David Bornstein, co-founder and CEO of the non-profit Solutions Journalism Network, calls journalism’s “disastrous (if well-intentioned) theory of change.” Put simply, the theory says that to make the world better, it’s first necessary to show people how terrible it is. It’s a disastrous theory, says Bornstein, because rather than inspiring engagement, it fosters depression, anxiety and fatalism:

If you keep people focused on the violence in the world, on the corruption in the world, on the untrustworthiness of other people, you’ll create a situation where people are more fearful, more protective, more divisive. You'll create the conditions where people do not work across lines of difference. And that's exactly what’s needed to create a dystopia…you need people to be fearful and disconnected.

Rather than creating fear, says Bornstein, journalists need:

really skillful ways of telling stories that draw out the better angels of our nature, that draw out our capacity for connection, that help us be in conversation with people we disagree with profoundly. How do we create stories that create that kind of container? That's the question.

Helping create such a container is the mission of SJN. They work with news organizations around the world to train journalists in how to take a more holistic approach to news reporting – to educate the public not just on the problems of the world, but also, with equal rigor, how people are trying to solve those problems and what can be learned from their experience.

Adding this critical piece to the journalistic framework, says Bornstein, does more than create a more complete, and more hopeful, understanding of the world. It also has the potential to help the press regain the public's trust, particularly at the local level. That’s because to be successful, a solutions approach requires journalists to develop deeper relationships with their communities, forged through a deeper understanding of their interests and problems. Says Bornstein:

When news organizations ask communities what they want, the first thing they say is ‘we want news that helps us solve our problems.’ And when news organizations then ask what those problems are, they get a list of things that are real pain points in people's minds.

And then the news organizations say, ‘okay, you told us that you're really concerned about the mental health of your teens…we're going to do some research on understanding the drivers of this problem. And then we're going to look at whether or not there are places in our community, or perhaps other communities, or maybe even in other countries, that can help us understand how to respond to these problems.’ And then they’ll bring that back to the community and say, ‘let’s talk about this, let's talk about some of these ideas.’

If you want to really rebuild trust among your audiences, in a time of intense partisan polarization, you need to be able to speak to people at that level, you need to be able to show that you care.

It’s very hard to show people that you care if what you do every day is tell them another thing they need to worry about. You may think, as a journalist, that that's your job. But that's not empowering people in any way. Or frankly, respecting them, respecting what their nervous systems can handle.

Journalism that respects people might be the best way to convey what Solutions Journalism is really all about. And it might explain why my conversation with David left me feeling a lot more hopeful about the role journalism can play in healing our democracy.

I invite you to listen to the entire interview. What I’ve shared here only scratches the surface of this empowering approach to journalism.

I was kind to a stranger. Twenty minutes later, I regretted it.

An unexpected encounter started off good, went bad, and then got good again.

I was flying home after facilitating my Difficult Conversations workshop at Idaho State University. It was the first leg of my return journey, a puddle-jump on a small turbo-prop from Pocatello to Seattle. It was a short flight, but long enough to teach me something.

During the boarding process, I had switched seats with a fellow traveler. I’d reserved an aisle seat, 14A, but the person who reserved 14B, the window seat, asked if we could switch places. I didn’t want to, but I could see she’d find the aisle more comfortable, so I agreed.

Twenty minutes into the flight, I started to regret my act of kindness. I was feeling cramped, and frustrated that I couldn’t stretch my legs. Regret soon morphed into resentment, and I began to stew. Why had she asked to switch? If I’d wanted the window seat, I’d have reserved the window seat! And she’s not even that much bigger than me, she would have been fine sitting in the window seat!

I let this fruitless internal dialogue rage on for a minute or two, and then finally interrupted myself long enough to point out that I was undoing any personal benefit I might have received from being a nice person. Rather than the positive vibes that come with being considerate of others, I was encasing myself in the emotional equivalent of barbed wire – every resentful thought a painful poke at my insides.

So, taking a lesson from my workshop, I decided to refocus my attention and looked out the window to the vista below. At that point we were flying over the snow-capped Sawtooth mountain range, and I impulsively tapped my seatmate on the shoulder and pointed to the beautiful view outside. She removed the earphones she’d been using and gazed out the window.

Looking out the window together gave us a chance to chat a bit, which opened another window, one that gave me a small glimpse into her life. She’d been in Pocatello over the Mother's Day weekend to watch her grandchild so that her daughter, a single mother, could get some rest. Now she was headed back to Seattle where a full week of work awaited her. I could tell she was tired. A busy mother helping another busy mother over Mother’s Day. It was a little sad – where were the men who should be celebrating them? – but also moving. By the end of this short conversation my resentment was gone. I felt good about my decision to switch seats, glad that after a tiring few days she at least had a more comfortable ride home.

This little episode reaffirmed for me the value of two related principles I talk about in my workshop: the importance of prioritizing the relationship over being right, and being able to see beyond our own story. Focusing just on my grievances — my ‘story’ — only amplified my discomfort and resentment. Focusing on the relationship forced me to widen my lens, to see beyond my story to take in the humanity of the other person – and to let that have a bearing, an influence, not only on how I saw the situation, but also on how I felt about it, and on how I responded.

A Hindu parable, recently sent to me by a friend, makes a similar point in a memorable way:

An aging master grew tired of his apprentice complaining, and so, one morning, sent him for some salt. When the apprentice returned, the master instructed the unhappy young man to put a handful of salt in a glass of water and drink it.

"How does it taste?" the master asked.

Bitter" said the apprentice, spitting it out.

The master then asked the young man to take the same handful of salt and put it in the lake. After the apprentice swirled his handful of salt in the water, the old man told him to drink from the lake.

"How does it taste?" the master asked.

"Fresh" said the apprentice.

"Do you taste the salt?" asked the master.

"No," said the young man.

At this, the master sat beside the young man, and said, "The pain of life is pure salt. But the amount of bitterness we taste depends on the container that holds it.

“So when you are in pain, the only thing you can do is to enlarge your sense of things. Stop being a glass. Become a lake.”

In a difficult conversation, seeing beyond our story and strengthening the relationship is how we turn a glass into a lake. It reduces our bitter (salty) feelings toward the ‘other’ by enlarging “our sense of things,” making us more compassionate, more responsive and, yes, even more happy.

___________

Photo by Mohammad Arrahmanur on Unsplash.

Reflections on the Nature of Evil

Thinking about the Russian invasion of Ukraine reminded me of a very personal experience I had years ago — one that taught me something about the nature of evil.

(This short essay is also featured on my podcast).

Thinking about the Russian invasion of Ukraine reminded me of a very personal experience I had years ago — one that taught me something about the nature of evil.

I was going through a program to help me confront my past. Painful memories and emotions are not something we tend to want to relive, but the theory behind this program was that by doing so, the energy trapped in these negative experiences is released for more positive and creative purposes.

Confronting my past wasn’t just about facing how I’d been treated, however, but also how I’d treated others. During this 6-week program of intense personal reflection, I came face-to-face with my arrogance, my dismissiveness of those I considered “less than,” my disregard for the feelings of others, and just in general the pure selfishness of so many of my attitudes and behaviors.

At the peak of this intense experience, (or should I say at the bottom) I broke down.

In physics there’s something called the “uncertainty principle,” which states that we can’t know exactly both the position and the momentum of a given particle at the same time. Knowing more about one of those values necessitates knowing less about the other.

Facing the truth of our own humanity is a lot like that uncertainty principle. There are great things about us and not so great things about us – individually and collectively. But if we try to look at both aspects of our nature at the same time, if we continually expend energy balancing the scales, neither aspect is fully revealed. So it can be helpful to just focus on one of them, to see as clearly as possible what it teaches us about the human condition.

When I broke down I was focused completely on my dark side, the most negative aspects of my personality. Overwhelmed with emotion, I buckled over and sobbed, repeating to myself again and again, “I am Hitler! I am Hitler! I am Hitler!”

There it was, humanity’s symbol of the ultimate embodiment of evil, conjured up by my psyche for me to look at – and to see in myself.

I, of course, am not actually Hitler. But what I saw were the very qualities that, under certain circumstances, can lead in that direction: The insecurity over our own self-worth; the dehumanization of those we consider less than; the anger we feel over experiences of rejection and humiliation; and the self-aggrandizement, loss of perspective, and complete disconnection from our own moral compass that too often comes with having power over others. In whatever ways and to whatever degrees, such tendencies are part of us all.

Ever since that experience I’ve never looked at other people quite the same way. My righteous indignation over the greedy and intolerant behavior of others never reaches the same intensity. I can’t find the energy to hate other people, or turn them into inhuman monsters, no matter how egregious their behavior. To deny their humanity is to deny my own, and that I can no longer do.

This shift in perspective does not make me complacent. It does not diminish the energy and commitment I have to do my part to make the world a better place. But it does change how I go about it.

Being able to see aspects of myself in those who manifest humanity’s most harmful qualities not only keeps me from claiming the moral high ground, it also clarifies the harm in making that claim. Asserting the moral high ground only hides from us our own humanness, which has the unhelpful effect of making us very difficult for others to listen to. More importantly, it makes it impossible to acknowledge and address the true root cause of our ills – which is, in fact, our inability to confront our own role in creating these ills in the first place.

Rather than claiming the moral high ground, I’ve learned it’s more authentic and more productive to claim the moral humble ground, knowingly grateful that “there but for the grace of God go I.” It is from that place, and I believe that place only, that we’ll find the wisdom we need to heal our country and our world.

Three questions

We’ve been on a long journey. What have we learned about where we are, who we are, and what we are to do?

“The world will ask you who you are,

and if you don't know, the world will tell you.”

Carl Jung

A friend who served in the Peace Corps in Nepal in the 1960s once told me a wonderful story about taking a Nepalese village chief, who’d come to visit my friend in the U.S., on his first-ever ride in an elevator. It was in a multi-level department store, and as the elevator rose it stopped at each floor to reveal the various items on display.

During the ride my friend noticed that every time the elevator doors opened, the chief would look out in wide-eyed amazement. It turned out the chief hadn’t realized the elevator was moving – he just saw the doors close and open, and every time they did, a new world emerged. He thought it was magic.

That story made me think about our early human ancestors, the first to navigate life on the other side of the newly-opened door of self-reflective thought. I tried to imagine the impact of that massive disruption to the human psyche, as patterns laid down by eons of biological evolution suddenly receded to make way for a new kind of creature:

Closed door: Survival is guided by instinct.

Open door: Survival is guided by conscious awareness.

Closed door: No questions, no self-doubt.

Open door: Endless questions, endless doubt.

Closed door: Identity is a given.

Open door: Identity is a quest.

It’s mind-blowing to think about how it would have been to be among the first to step through that door, to suddenly confront an overwhelmingly mysterious and unpredictable world. To have to ask and answer three questions no species before ever had to: Where am I? Who am I? What am I to do?

Humans are tribal creatures, and when we reflect on our earliest beginnings we can see why. There was a lot to being human to figure out, and things would go faster and better if we did it together. So we gathered into tribes, where we learned to share responsibilities. Take on roles. Establish rules. Create customs. In other words, we developed culture. And in the process we gave ourselves a simple context for answering those three questions:

Where am I? In a tribe.

Who am I? A member of the tribe.

What am I to do? Follow the rules of the tribe.

By many measures the tribal model has been a huge success, and highly elastic – expandable up to the nation-state tribes of today (at least, so far). But it came at a cost. By organizing ourselves into tribes, our individual identity got absorbed into the collective, and suddenly what others thought of us became a vital preoccupation. Should the tribe ever decide we’re unworthy of membership, we might be banished, forced to face the world’s dangers alone – making tribal acceptance a matter of life and death.

Over time, however, this drive for tribal acceptance has mutated from being a means to secure our physical well-being to also securing our psychological well-being, which in our culture can feel under constant threat. Not a day goes by without repeated invitations to compare ourselves to others and to assess whether we’re “measuring up” to society’s standards. Should we find ourselves wanting, our primary options seem to be to either improve our standing through status-minded acquisitions, or to anesthetize the pain of social rejection with drugs, or to join a different tribe altogether – perhaps one that shares our grievances and outsider status.

While psychologists will tell us that our need for social approval is what “sustains cohesive societies,” it appears the exact opposite is true. If everyone is looking to everyone else for approval — and I mean everyone, even the rich and famous and beautiful – the culture has no center of gravity, no North Star, no transcendent reference point that can guide our individual, and therefore collective, evolution. We become a dis-individuated tribal mass, all trapped in the same crazy hall of mirrors where our perceived self-worth rises and falls based on what everyone else reflects back to us. This is the world of social media writ large. The outcome? A society that’s increasingly fearful, divisive, narcissistic, depressed and anxious.

It’s also a society vulnerable to the psychology of the mob. When our desire for belonging and acceptance overrides the directives of our own inner compass, we become subject to misdirection, manipulation and coercion. Especially by those who have their hands on the levers of power.

The Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung understood the dangers of this dynamic well. In a book called “The Undiscovered Self,'' written in the aftermath of World War II, he says that when the mass “crushes out the insight and reflection” of the individual, it will necessarily lead to tyranny if ever “the constitutional State should succumb to a fit of weakness.” (Meaning, should it begin to lose its authority.)

It’s in this “fit of weakness,” he says, that we open the door to a “subversive minority” of individuals who “hold the incendiary torches ready with nothing to stop the spread of their ideas except the critical reason of a single, fairly intelligent, stable stratum of the population.” He then adds, pointedly: “One must not overestimate the thickness of this stratum.” (Italics mine.)

Clearly, Jung’s warning resonates today. Our institutions, ravaged by a tenacious and deadly virus and overwhelmed by numerous social, political and environmental crises, are indeed in a fit of weakness. The incendiary torches have been lit – at home and abroad – and the resultant anxiety many of us feel reflects our concerns over whether there’s an “intelligent, stable stratum” thick enough to stop their spread.

A more important concern, however, is whether we know what it means to be part of that stratum. I believe it means having answered our three questions – Where am I? Who am I? What am I to do? – in a context that extends well beyond the tribe. Answers that recognize our common humanity and our inalienable self-worth. Answers that give us the reason and the resolve to listen to and understand the opposing point of view – even if it means the harsh judgment, or even condemnation, of our tribal peers.

This is how the stable stratum is formed. This is how we defuse tensions rather than exacerbate them and reduce the heat of conflict rather than stoke it. This is how receptivity, compassion and moral reasoning – all crucial to our survival yet beyond our reach in times of fear – are brought back within our grasp.

Evolution’s elevator has not been staying still. Doors have been closing and opening all along, each time revealing new insights into the nature of our world as well as ourselves. Most striking: Confirmation from science that reality truly is a single whole, and, though our five senses deny it, we are of that wholeness, inseparable.

If we haven’t kept up with these insights and pondered their implications, now would be a propitious time to do so.

Keeping the Bonds Between Us

“There are people so consumed by hate that they are worth fearing. But here's the radical belief I have: I still think that what even those people really crave, is to be heard, and seen.” — Mónica Guzmán

A few weeks ago a new book came out called “I never thought of it that way: How to have fearlessly curious conversations in dangerously divided times,” by Mónica Guzmán. The title caught my attention, and I rather impulsively emailed Mónica to ask if she'd be a guest on my podcast. She immediately replied, “yes!”

Now it was time to read her book.

I didn’t have high expectations. I’ve read a number of great books on the subject – and wrote one of my own — and doubted this one would tell me anything new. I was wrong.

The best way to describe what Mónica’s written is to compare it to a kind of magical guidebook to a foreign land. A typical guidebook gives you some history, the essential places to visit, and tips on where to eat and stay. But a magical guidebook – the one you wish existed – would immerse you in the culture, make you feel the excitement of actually being there, and somehow even give you the language skills you need to connect with everyone you meet. In other words, you’d be fully prepared to get the absolute most out of your journey.

If you find yourself wanting or needing to visit the land of difficult conversations, “I never thought of it that way” is about as close to a magical guidebook as you’re likely to get.

You can go right to the podcast with Mónica, or read on for some highlights from our conversation (edited for clarity).

Q: You write that as a journalist, every one of your now thousands of interviews “was something everyone craves but rarely encounters: a conversation bent on understanding without judgment.” That struck me as really a powerful statement, because it speaks to something so fundamental in us, our need to be seen, to be accepted for who we are. But we don't give that to each other very often. Why is that?

A: A: One thing that stops us from seeing the “other” is our own desperation to be seen. There's a lot of great philosophical writing about solitude and conversation. My favorite book on this is Reclaiming Conversation by Sherry Turkle. She talks about how coming into a conversation fully means being open and able to listen to the other person. But when you have things that you're in turmoil over, sometimes your “listening” is really just you trying to be heard. So sometimes it takes a bit of solitude, some time to be curious about yourself, and to be honest with yourself about the places you're struggling, before you're able to come fully into a conversation – before you're humble and open enough to really make it an exchange, instead of a turn-taking type of exercise.

Q: You have an acronym, SOS, which stands for Sorting, Othering, and Siloing. We sort ourselves into like minded groups, separate ourselves from others who think differently, and over time that creates silos – environments that continually reinforce our view of the world. As a result, you say, we’re “steering ourselves away from reality.” That struck me because from an evolutionary perspective, no species does very well if they're not able to see reality. So, could you speak a little bit more to what's at stake here, by not getting out of our silos?

A: Oh, a lot. The social sciences are giving us a lot of evidence that many people are living with more anxiety and more fear of other people than is justified. There are studies that show that when people on one side look at the other side, and are asked to guess at the views on that side, we grossly exaggerate those views….we believe they’re more extreme than they are. And of course, extreme views are tied with more harm, right? And so they’re a greater level of threat.

When we get out of our silos and have conversations with actual people, it puts a check on the misperceptions swirling around in the media and in our silos, about who those other people are, and what's motivating them to make these choices that confound us at the ballot box or anywhere else. Imagine reducing the fear and anxiety with which we're living, and with what we use to make our decisions about our everyday lives!

Another consequence is that people are breaking their relationships with their relatives and with their friends all the time. Because the differences are too much. It’s too hard. It feels that way at least. But that's the key word to me, feeling. Again, how much of our decisions to break those relationships is based on a clear view of the disagreement versus what might be exaggerations? And if we could clarify those exaggerations, could we maintain the relationships?

Q: This gets to the concept of bridge building, of finding ways to connect across our differences. But you say something that at first glance is kind of intriguing. You say that “the most important thing to do with a bridge is not to cross it, but to keep it.” Can you say more about that?

A: One of the mistakes we make when we enter into these conversations of difference, when we're ready to be curious, is we demand that the other person show up on exactly our terms in exactly the ways we want. And then when they don't, we're like, “Well, that was a waste of an hour of my life.” And then we burn the bridge.

I have a relative I absolutely love who doesn't vaccinate her son or herself. We have huge disagreements about the COVID vaccine, enormous. But I'm not spending my time in conversation with her telling her she's wrong, or any of that. And she's not spending time telling me I'm wrong. When we talk about the vaccine, we talk about how we came to trust what we trust and how we came to believe what we believe. And that becomes really interesting.

She's one of the healthiest people I know. So obviously, it's not a lack of value for health. But she has a deep suspicion of wealth, and of corporate greed. She has a lot of questions about the companies making the vaccine and the role they play in this... just deep distrust. And I find it fascinating when we talk about it.

The important thing is that I'm there for her, so that if someday she thinks to herself, “okay, maybe I'm wrong about vaccines,” she’ll feel free to give me a call and we can talk it over. Or maybe it’s the other way around. Maybe one day I’ll think I’m wrong and give her a call.

What matters is to keep the bridge open. Because we can, we can keep it open.

Q: One of the things that’s missing in our national dialogue is the inspiration for why we should to talk to each other, why we should get beyond the condemnation and the judgment. Instead, there's so much fear, which is a really interesting thing, how fear operates in terms of keeping us apart.

A: There are people so consumed by hate that they are worth fearing. But here's the radical belief I have: I still think that what even those people really crave, is to be heard, and seen. And I know that people are like, “but not by me!” Ok, not by you, that's fine. But the more glue that we can build between each other as people, the more likely it is that those who are destined to be so consumed by hate that they really kind of sin against humanity — they will be caught before they get there, they’ll be held before they get there, and maybe they won't get there at all. But that'll only happen if we keep those bonds between us and make it possible.

Q: I'm wondering, how did you come to be so totally convinced of what you just said?

A: One thing that's coming up for me is, I guess, a close observation and reflection on the things going on in my own mind. There have been so many times where my reaction is judgment. And even in the moment I might think to myself, I hate that person, what they just did to me. And then if I slow down, take a little time, if I get curious about what's going on, I'll see my own role in whatever happened. I will see different perspectives on what happened.

And usually what I need to do as part of that process, is to allow whatever the emotion or concern is, in my gut, to be heard by me or by someone else. Like, I need it to be understood that I'm under a lot of pressure right now. Or that, I'm really worried, you know, that this project or this thing that we're trying to do is going to go south. Once I'm able to express that, and see it acknowledged either by myself or by someone else, it all changes.

I was just at the Smithsonian Museum of American History. And they have an exhibit with Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz. And they show the page on the screenplay, where it went from black and white, to full color. And that's what it feels like, I was looking at everything in black and white, and then suddenly it goes into full color. And everything's fine.

So maybe that's an unusual way to answer the question. But because I see that dynamic in me, you know, even though it doesn't go all the way to like I want to kill someone, I can see how it could if you kept it going!

I mentioned in my book that I did an interview with a convicted murderer, and then I watched him die, get executed, in Texas. And it was really painful to do that, to interview him. And also to interview his mother. And the whole time I was like, this is about so much more than just him. He grew up really poor, and in a terrible situation. And I'm not saying that excuses what he did. Obviously, it does not excuse what he did. But it was just, I saw in his life, so many opportunities for someone to love him that weren't met. And that's what hate is right? It's the absence of love. So, again, I look around and I see everybody removing their love from each other.

I can't believe you've gotten me to this place…I have a little rule in my head, never bring up love because that's when people think you're getting too squishy. But you know, we sing about love. We have love songs all the time, but we don't talk about it.

Love is acceptance. That's what it is. It's acceptance.

I encourage you to listen to the whole interview. You’ll find it here.

The strange, attractive power of conflict

A couple weeks ago I was at our local gym. One of the policies in the COVID-era is that after you use a piece of equipment, you need to wipe it down with a disinfectant. There was one young man, however, who was not following the policy, and an older man confronted him about it. The younger man ignored him, infuriating the older man.

A second older man, witnessing the episode, confronted the first older man, challenging his right to say anything at all to the younger man, and that he should “stay out of his face.”

A third older man – me – now finds himself getting mad at the second older man for hypocritically getting angry at the first older man, but thankfully knows better than to get involved.

Ignoring, for just a moment, that this story involves only men, I want to make a different point: It’s a great example of what Amanda Ripley, author of High Conflict: Why We Get Trapped and How We Get Out, calls the La Brea Tar Pits scenario.

You may or may not know about the La Brea Tar Pits. It is, Amanda told me in my latest podcast interview, a natural asphalt spring in Los Angeles that’s been around since the last ice age. Interestingly scientists have found “more than three million bones trapped in the depths of these pits.” That includes “mammoths, sloths and more than two thousand saber-toothed tigers.” So how did they get there?

“Research suggests,” Amanda said, “it must have started when a large mammal, maybe a bison or something, wandered into a tar pit and got stuck. And then the Bison probably started making noises of distress, attracting other animals who were delighted to find a giant bison just sitting there. So they go for the bison, and then they get trapped. So now they're howling, which draws the scavengers in, and the next thing you know, you have thousands and thousands of these creatures, each one slowly, over a period of time, sinking into the depths of these pits.”

This, says Amanda, is a metaphor for the attractive power of conflict: It pulls you in. I’m sure you’ve experienced and/or witnessed the dynamic in your own life. I find the power of the Tar Pits metaphor helpful. It was in my mind that day at the gym, and was one reason I had the good sense not to get myself drawn into that particular conflict.

The gym story also illustrates another important dynamic that can trigger high conflict. It’s the power of humiliation, which Amanda calls the “nuclear bomb of emotions.” By not even acknowledging the older man, the younger man was humiliating him, telling him he was not even worth responding to.

It’s interesting to think of the ways we can be the agents and victims of humiliation. I’ve noticed it while playing games. If I beat my wife too badly in ping pong, she starts to feel humiliated and mistreated. I tended to dismiss that as poor sportsmanship, until I experienced similar feelings of humiliation when being trounced in pickleball. Suddenly, I understood my wife’s emotions.

These are just two of many helpful insights into the dynamics of high conflict that Amanda shares in her book and on my podcast. Some of the things we talk about, in addition to the La Brea Tar Pits:

The four "trip wires" that lead to high conflict, including "the power of the binary."

Why often the best thing you can do in a conflict is first "get straight in your own head."

How finding the "understory" of a conflict can be a source of liberation.

How to creatively break the patterns of high conflict by "stepping out of the dance."

What it means and why it's important to appeal to a "transcendent identity."

And much more (my favorite: Amanda's "food in the fridge" conflict).

I hope you’ll check it out.

“That’s where all the juice is.”

Reflections on developing a mindfulness practice.

Just before the holidays I interviewed Brett Hill for my podcast. Brett is a mindfulness coach who’s been studying, practicing, and teaching mindfulness and other forms of meditation for decades.

At first I was hesitant to do the interview, only because mindfulness as a topic seemed to be suffering from over-exposure. Hardly a day goes by without a new study touting yet another benefit of a mindfulness practice. Among the things we’ve learned so far: being mindful improves relationships, helps relieve stress and anxiety, increases our capacity to deal with adverse events, treats heart disease, lowers blood pressure, reduces chronic pain, improves sleep, strengthens our immune system, improves our memory, and – get this – even reduces cell aging. Whew!

That's an impressive list, but written out like that, it lacks a certain context or coherence. What exactly are we doing when we become mindful? What’s changing in us that leads to all these benefits?

The larger context for Brett is that a mindfulness practice is a journey for “becoming whole.” A journey to “stop acting out of our woundedness” and instead be in a state of vibrant connection to the present moment. The “practice” part is becoming attuned to our body and our feelings so that we know when we’re not connected – when we’re operating from a place of woundedness. Only then can we attend to our woundedness and discover its deeper source, giving us more conscious control over its influence.

All of this brings to mind a supporting passage from Gary Zukov’s book, The Seat of the Soul:

The road to authentic power is always finally through what you feel, through your heart…If you do not know what you feel, you cannot come to know the splintered nature of your personality, and to challenge those aspects and those energies that do not serve your development.

The journey toward wholeness requires that you look honestly, openly and with courage into yourself, into the dynamics that lie behind what you feel, what you perceive, what you value, how you act. It is a journey through your defenses and beyond so that you can experience consciously the nature of your personality, face what it has produced in your life, accept that, and choose to change.

I was interviewed for a podcast recently and shared a personal story that relates to what Brett and Gary are talking about. I’m 66 years old, and when I go to the gym there’s often a pod of high school guys working out together. There’s a certain swagger among some of them that I realized set me off, and caused me to think negative thoughts about them. Once I became aware of those thoughts I was able to ask myself, where do these feelings come from? Why am I bringing them into this moment? I don’t know these kids. They might be the nicest people in the world.

That led me to a connection I hadn’t made before. Growing up there were certain kids who liked to pick on me and the feelings of anger, hurt and resentment were still lurking in my unconscious. These kids, innocent bystanders all, triggered those feelings. Making that connection allowed me to withdraw the negative perception I had of them.

The challenge of all this, of course, is that in the moment of conflict, looking at “the dynamics that lie behind'' what we feel is often the last thing we want to do. It might mean confronting painful memories, or assuming a level of responsibility for ourselves we’d rather not. We’d rather stay justified in our feelings, giving them free range, and in the process doing damage to our relationships.

That resistance to exploring our feelings and our reactions, Brett says, is why we need a mindfulness practice: “If you want to be mindful and present when you're under stress, you have to practice when you're not. Just like if you want to play a piano in a concert, you have to practice when you're not in a concert.”

And what are the rewards of such a practice, of becoming more mindful? Says Brett:

“That's where all the juice is, that's where all the lusciousness of life is, that's where all the richness is – in the connection and the depth of rapport and appreciation that comes from living in the world in a way that feels like you're really in it, versus just kind of skimming across the surface.”

You can listen to my whole interview with Brett here.

When it gets dark, share the light.

Advice given to someone in conflict feels relevant to these times.

Perhaps because of the media focus this week on the January 6th Capitol riot, I woke up the other day with a short fable planted in my head – one that’s been written in one form or another a zillion times. A small village finds itself plunged into darkness. In the village square, people are walking about, unable to see each other clearly. They start to bump into one another, causing accidents, arguments and misunderstandings.

Then one villager has an idea and lights a candle to see better. A number of other villagers notice, and light candles of their own – allowing them to walk about freely, offering assistance without contributing to the chaos.

Not everyone, however, catches on. Some villagers — for whatever reasons — never light a candle, and continue to fumble in the darkness. But rather than avoid such people, the candle carriers encircle them – the glow of their combined light helping to reduce the darkness for everyone.

I think of people who know how to engage others in constructive dialogue around contentious issues as candle carriers. What most distinguishes them is that they share their light — their goodwill — without strings, without preconditions. They know there’s no litmus test for who’s worthy of the candle’s light.

I meet a lot of candle carriers through my workshop, and I’m incredibly grateful for them. Linda (not her real name) is one. She contacted me several weeks ago for advice. She’d been through my workshop and wondered if I’d coach her on a conflict she was having with her niece. I’m not a therapist, but I agreed to talk to her to see if any experience in my life could help her think through her own situation.

With Linda’s permission, I thought I’d share our correspondence because to me it highlights what it means to be a candle carrier. You might also find aspects relevant to your own difficult conversations.

Without going into details, the gist of the conflict is that Linda’s niece had done something that hurt Linda’s feelings and, wanting an apology, Linda confronted her about it. But rather than apologize, Linda’s niece went on the attack, saying she had nothing to apologize for, and in fact if anyone needed to apologize, it was Linda. The niece also vaguely referred to a number of other things Linda had done in the past that the niece was still angry about, adding yet more complexity to the dynamic.

The anger and intensity of her niece's response caught Linda off guard. That’s when she reached out to me. Specifically, she wanted to know how the principles of my workshop could be applied in a situatIon like this.

My first suggestion was that, before reaching out to her niece, she take the time to understand her own contribution to the conflict. I reminded her of the second “new survival drive” we discussed in my workshop: “See beyond your story.” We all look at the world through the lens of our past, and hurt feelings in the present almost always connect back to earlier life experiences. By making that connection conscious, the intensity of our emotions diminishes and we’re able to take responsibility for our reaction rather than blame it on others. No longer trapped in our own story, we’re able to see more clearly. That’s when we stop being part of the problem and start being part of the solution.

It was not easy advice — but as a candle carrier, Linda took it to heart. Days later she sent me this email:

Thank you for taking the time to meet with me last week. Although it was difficult, I was able to honestly (I hope) examine how my story caused me to react to my niece in a way that began an unfortunate chain of interactions. What became apparent is that my story is my humanness.

I love that line: “My story is my humanness.” Ain’t that the truth! There’s a release of self in that line, an acceptance of our humanity that’s as freeing as it is humbling. I think a lot of the pain and suffering in life comes from unrealistic expectations of ourselves. When we can let go of those illusory expectations we can stop resisting our own humanity, tapping into a well of compassion for ourselves as well as others.

Having reflected on her own part in the conflict, Linda decided to draft an email to her niece and reached out to me again for my thoughts:

I'm wondering what you think about addressing some of the points, actually accusations, she brought up in her response to me. On one hand doing so seems like it might muddy the already treacherous waters, yet on the other hand, failing to acknowledge anything she wrote seems like a disrespectful dismissal. I don't know which route to go, and, if I decide to address some of what she said, how to do so without "defending" myself and continuing a back and forth argument. One of her accusations is partially true. I could own the part that's true and say something about the part that's not.

At any rate, I'd be interested in hearing your thoughts.

Here’s how I responded:

I don’t know the specifics of this situation, just the outlines, so my comments will be general, based on my own experience. I offer it knowing you’ll decide what feels relevant or appropriate to you.

Given what you’ve said about your niece, I’m guessing a “rational” conversation about who’s responsible for what is presently off the table. She’s not ready. She’s still in a highly emotional and reactive state.

Given that, I recommend removing yourself from the equation. Release any need to be understood, for things to be fair, to have your point of view expressed. In the language of my workshop, those are all the desires of our “story self.” It wants to be acknowledged. What I call our “un-story self” — that deeper, intensely grounded sense of self we experience when we are “self-abandoned” — has no need of that acknowledgment. Tap into that. Trust that.

Then have one goal: Imagine you’re a crisis interventionist. Your job is to help someone who’s in a troubled state of mind get into a healthier state. It’s not personal to you. You’re free to say/do whatever is needed to help your niece.

As a crisis interventionist you know the first step is to acknowledge that her feelings are legitimate. Not legitimate in the sense that you’re somehow responsible for them, but legitimate in the sense that they’re the natural outcome of her own present state of being — her own story.

So give her that acknowledgment, and then give her a reason to trust you. Something to the effect that, “The last thing I’d want is to have you feel the way you do. I love you, our relationship has always been special to me, and anything I've done to hurt you I’m sorry for. I hope you can forgive me.”

If that last sentence trips you up, let me clarify: The spirit in which you ask for forgiveness has nothing to do with taking on blame; it’s not a statement of needing forgiveness for yourself. You ask for forgiveness out of an awareness that this is what the relationship needs to move forward, and because you know that by forgiving you for her perceived trespasses, your niece is taking an important step in her own healing. The act of forgiving is primarily for the benefit of the forgiver, not the forgiven. By forgiving you, she is removing her own obstacles to the relationship. Obstacles she put in place.

More advice that’s not easy to take, but Linda said she found it “instructive and helpful,” and that she’d use it as a guide in writing her email to her niece. She chose to send the email on December 16th, in honor of South Africa’s Day of Reconciliation.

In our last communication Linda shared that she’d not yet heard back from her niece. But she wasn’t ready to give up. “I’ll wait a few months and then try again,” she said.

Sometimes that’s just the best we can do. To be patient, to leave the door open. Because you never know when the other person might walk through.

In the meantime, Linda has the increased self-awareness and peace of mind that comes from having done the work of candle-carrying. She’s glad she did that work. She’s glad she sent the email. Because, she said, “living with personal/emotional courage is important to me.”

In this time of relative darkness, it’s important to all of us.

"It's all about love": Three lessons from a crisis interventionist on how to de-escalate conflicts

In a world awash in difficult conversations, it helps to be trained in crisis intervention.

My latest podcast guest, Joe Smarro — featured in the Emmy award winning HBO documentary, Ernie and Joe: Crisis Cops — taught me something about navigating difficult conversations: It helps to be trained in crisis intervention.

For 15 years Joe was an officer with the San Antonio, Texas police department. The last 11 of those years was with the mental health and crisis intervention unit. His job: de-escalate dangerous confrontations with those suffering from mental health traumas. It’s the kind of confrontation officers face frequently, and that accounts for one in five people killed by the police. Yet in 11 years, Joe never once had to resort to force. His only weapon, he says, was his ability to communicate.

After gaining national attention for his approach to crisis intervention training, Joe left the police force and founded, together with his business partner, Jesse Trevino, Solution Point Plus, where he now delivers his training to law enforcement officers and other first responders around the country.

What got me interested in Joe's work was discovering that the principles underlying his training are exactly what I talk about in my Difficult Conversations book and workshop. I figured he’d have a lot to say about how these principles work in real life, and the positive impact they can have in even the most highly charged situations. But there was something else, too, that got my interest. Embedded in Joe’s approach is an essential ingredient crucial to his success. I’ll talk more about that ingredient in a moment. First, though, I’d like to walk you through the principles that underlie Joe’s training.

Principle #1: It starts with you. ”The first step of effective de-escalation is self awareness.” says Joe. In other words, his training isn’t just for you, it’s about you — it’s training to help you gain the self-knowledge you need to not get caught up in the other person’s problem. That means having an intimate relationship with your own emotional landscape — the past hurts and traumas that, left unconscious or unresolved, can become landmines for other people to step on. It’s when we get emotionally triggered that conflicts escalate, and have the highest potential for turning violent — verbally or physically.

Joe came to this first principle through personal experience. After joining the police department’s crisis intervention unit, he realized he wasn’t following his own advice, and that his own life “was a mess.” In his words:

The first two years I was on that unit, I was a total hypocrite...I would show up every day telling people, "If you would just take your medications, if you would just make your doctor appointments, if you would just do the right thing, you wouldn't have to deal with law enforcement like this. It's not that hard.’"

But then I would go home, and I'm on my second divorce at the time, and I'm drinking way more than I should, and I'm sitting in my apartment, by myself, staring at my gun belt, thinking, ‘I don't want to do this anymore...I'm tired of sucking at life. I'm a mess.’

And as my second wife was leaving me, she said, “Hey, there’s something seriously wrong with you. You should get help.” And that's when I went to the VA. And I was diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and Persistent Depressive Disorder. And I've been in treatment ever since. That was probably 10 years ago, and I've never left.

But what I realized, that was so profound for me, was that as I really dove in and became super curious about me, myself, who I am, why I do the things I do, and how I got to where I am, the more willing I was to help myself, and the better able I became to help other people.

Principle #2: Focus on the person, not the problem; focus on connection, not correction. As I’ve mentioned, in 11 years with the crisis intervention unit Joe never had to use force to get voluntary compliance from the distraught and potentially violent person he was trying to help. How did he do it?

“The goal has to be connection before correction,” said Joe. “You're not going to get someone to comply with you if you don't have a connection established. And this is a very foreign concept for people to understand, especially in policing, where we’re trained to come in from the position of authority: You will do what I say just because I'm in charge.”

Instead of forcing compliance through authority, Joe teaches people to gain compliance through curiosity and listening. It’s another principle rooted in his own experience:

I was always a very curious person, I always knew that my eyes were deceiving me, that what I'm looking at isn’t the whole story. Something happened to get this person to be in this state. So I want to be curious about what happened. Like, let's not just react to what we're looking at, but rather respond to what we know. And we're only going to know things by asking questions, and being patient. And it was really by developing this approach within myself that I now teach it to others. And we've had incredible results.

Another key to getting compliance is understanding people’s need for control. No one likes being told what to do or what to think, or being made to feel diminished in any way. A far more effective approach, says Joe, is to model the behavior you’d like to see. To make the point, he has a twist on the old adage, “You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink.” Making it drink, says Joe, isn’t our job. It’s to make the horse thirsty, because a thirsty horse will find its own water.

So how do you make someone thirsty? “You inspire them,” said Joe. “You educate them, you advocate for them, and you demonstrate for them. Nowhere in there do I tell people what to do. It's simply about showing them the way.”

Principle #3: It's all about love. Yes, Joe uses the “L” word, even with police officers. For Joe, love is the antidote to what ails us, the fundamental corrective for a society wedded to punishment rather than mercy, condemnation rather than compassion. As he told me: